Just before midnight on 21st October 1904, Russian warships were sailing across the North Sea from their base at Libau in the Baltic Sea. These warships were on an 18,000-mile voyage to engage the Japanese. At the time, Russia and Japan were locked in a struggle to establish and exert their imperial power in the Far East. The incident that occurred late on the night of 21st October caused shock, horror and outrage, not only in Hull, but across the country, leading to escalating tension between Britain and Russia, and a real possibility of military conflict between the two. This blog recalls the North Sea Incident, known to some as the Russian Outrage.

As the Russian fleet made its way across the North Sea, south of the Dogger Bank was the Gamecock fleet of steam-trawlers. The Gamecock fishing fleet, around forty in total, was one of the largest and sailed out of Hull. They operated as a fleet, often staying at sea for months at a time. Trawlers would catch the fish before transferring the catch to faster steam cutters, which would land the fish at places such as Billingsgate in London.

The night of the incident was misty and drizzly. The trawlers were spread over some miles. The fleet itself was positioned south east of the Dogger Bank, around 200 miles off Spurn Point. To help with navigation the fleet used rockets and coloured lights to signal which direction they were to sail. Through the mist and rain several vessels appeared. Some of the crews were aware the Russian fleet had left the Baltic and would be heading towards the English Channel. At the time some fishermen believed these to be British warships on maneuvers.

To identify themselves, the trawlers used flares and lights. Upon seeing the trawlers, the Russians used their powerful search lights, illuminating the trawlers. No sooner had the Russians illuminated the trawlers, they started firing. Initially, some believed it to be blank shot, but very quickly the trawlermen were all too aware they were under attack. Shells, the size of cucumbers embedded themselves within some of the trawlers. One fisherman is alleged to have held two fish aloft, indicating to the Russians that they were fishermen. One trawler skipper recalled how they could see the faces of the Russian sailors and that they must have realised those they were shooting were trawlers.

Some trawlers were in the process of hauling up their nets, but in desperation to escape, cut their nets. Some extinguished their lights to avoid being seen. The firing continued and lasted for around half an hour. After the firing had ceased, several trawlers were damaged. One, the Crane, sank shortly afterwards, not before the crew and the bodies of its dead skipper and Third Mate were recovered from the deck. The Russian fleet then continued in its progress towards the English Channel. News of the incident was made public on the evening of 23rd October. Initial reports were sketchy, but as men and trawlers returned home, the picture of the attack became clearer. The Mino had taken significant damage, its crew struggled to keep the vessel afloat. However, it was the Crane that bore the brunt of the attack, sinking shortly afterwards. The two crew that lost their lives were George Smith and William Leggott. Smith's son was aboard the Crane. Aged fifteen, this was his first time at sea. Miraculously he was uninjured and survived along with the remaining crew. Altogether one trawler was lost and five more damaged.

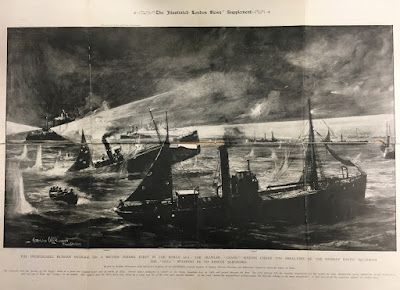

|

| Depiction of the North Sea Incident from the Illustrated London News Supplement, 1904 [Ref: L.639.22] |

In the aftermath there was huge public anger. None more so than in Hull were the Mayor of Hull condemned the act, referring to it as the ‘Russian Outrage’. Elsewhere there were noisy protests outside the Russian Embassy in London and the incident led to a serious diplomatic conflict between Russia and Britain. With tensions increasing, the British Government put its Mediterranean, Channel and Home fleets in a state of readiness. The British demanded an inquiry to ascertain the facts and to gain compensation for those that had suffered.

The funerals of George Smith and William Leggott took place on Thursday 27th October. From Park Street to the cemetery at Spring Bank, people lined the streets. Smith's coffin was brought out of his house on Ribble Street and put into a horse drawn hearse. The procession was led by the Chief Constable of Hull and the Salvation Army. The hearse followed, as too did the mourners and men of the Gamecock fleet, which included owners and directors. This was followed by the coffin of William Leggott, the Crane's Third Mate.

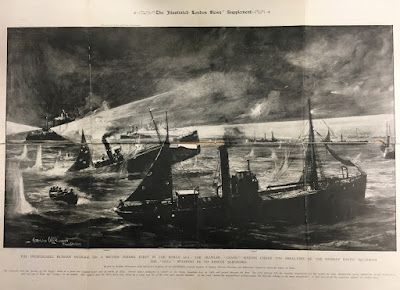

|

| Funeral of George Smith and William Leggott, 27 October 1904 [Ref: L RH/1/206] |

A public relief fund was setup and donations reached the city from wealthy individuals. Queen Alexandra contributed £100, while the King gave 200 guineas. By the 5th November a total of nearly £1000 had been raised.

The Russians, however, were reluctant to accept responsibility. The version of events given by the Russian Admiral was that the fleet was provoked by two torpedo-boats, which had advanced to attack the Russian fleet. The Russian Admiral went on to claim they endeavoured to spare the fishing boats as a result. He also accused the fishing vessels of conspiring with the Japanese torpedo-boats and went on to say no warship could have acted otherwise and expressed his sincere regret for the unfortunate victims.

On 15th November the Board of Trade inquiry commenced at Hull. It took place in the Assembly Rooms. A series of eyewitness descriptions were provided by the fishermen involved. The testimonies all agreed the vessels had their regulation lights on. However, visibility prevented seeing any ships at a distance on that night. The fishermen reported seeing the lights of several vessels approaching from a north east direction. It was claimed the Russians observed the trawlers, but in groups the Russian ships began to fire. In an attempt to stop the Russians from continuing to fire, some of the vessels launched rockets into the air, which were used by the fleet to navigate. The Russians, however, continued to fire. It was reported the attack lasted between 10-30 minutes, but no less than 10 minutes. The inquest also established that no torpedo-boats were present among the trawlers and that no crew or members had being in the service of the Japanese Navy.

It was also determined that search lights from the Russian vessels must have seen the lettering and numbering on the vessels to indicate that they were in fact trawlers. The firing, however, continued and the only projectiles found aboard the trawlers were ones from the Russian Navy.

A case of mistaken identity was one thing but what happened in the aftermath was determined to have been an act of belligerent behaviour by the Russian Navy. At about 7am the next morning, another trawler, Kennet, was fired upon by a Russian warship. The warship stopped for three to four minutes before then steaming away.

The inquest found the trawlers of the Gamecock Fleet were fired upon without warning or provocation, by several warships of the Russian Navy, and that the firing continued for at least 10 minutes. The Russian search lights should have established that these were in fact trawlers, not torpedo-boats belonging to the Japanese Navy as it was claimed. The firing continued deliberately, without reason or justification and the Russian vessels failed to render any assistance or ascertain the condition of the craft or crews. In the end, the Russians were found liable for compensation, which was distributed to the fishermen and the vessels owners to pay for damage and loss of income.

The inquiry into the deaths of George Smith and Henry Leggott concluded that both died in the company of about forty to fifty vessels of the Hull fishing fleet. Although regulation lights were used to indicate they in fact were fishing vessels, both were killed by shots fired without warning or provocation, from Russian war vessels at about a distance of quarter of a mile.

Tensions and anger eventually subsided. In Hull bitterness remained. Charles Henry Wilson was one of those who had a vested interest in the Wilson Line’s Baltic trade routes. Wilson knew too well the position of his of his vessels and crew when visiting Russian ports, and this could be jeopardised should there be any political fallout from the incident. Wilson stated it was simply a case of mistaken identity. Wilson, however, was heavily criticised for his comments.

Today the Russian Incident is all but forgotten outside of Hull. A reminder of the incident stands on Hessle Road, erected in memory of the two fishermen who lost their lives on 21st October 1904. A third fishermen, Walter Whelpton, skipper of the Mino, died in May the following year, as a result of shock.

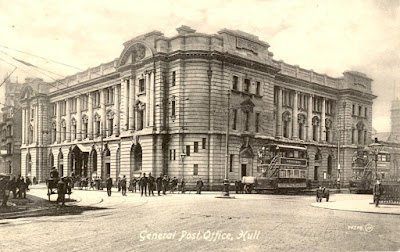

|

| Plaque commemorating George Smith and William Leggott [Ref: L RH/1/224] |

If you wish to explore the event in more detail, the Local Studies Library at the Hull History Centre has several books available to read. These include Arthur Credland's ‘North Sea Incident: 21-22 October 1904’ [Ref: L.639.22]. Also available are a number of postcard images depicting the incident, which are held within the Local Studies Renton Heathcote collection at the Hull History Centre [Ref: L RH/1/203-224].

Neil Chadwick, Project Officer, Unlocking the Treasures

![Unveiling of the statue of William de la Pole, originally situate on Prospect Street, before being relocated to Nelson Street by the pier [C DI] Unveiling of the statue of William de la Pole, originally situate on Prospect Street, before being relocated to Nelson Street by the pier [C DI]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhToxMwPDVuN63uPz3ydB5Jy17V804DV-F3WXUfujhWoPMInVDbT4rwaSTKzxHufOaLMkn9owD7EOBZbxfHS8mfbpQ2VopJcDHdOSfoSdve1kzm0jt6lRK3atVsKla8G6XzJFvAVcWQDA/w294-h400/Unveiling+of+de+la+Pole+statue.jpg)