In this first of a two-part blog, we recount the story of three Hull men who set out with the First Fleet to Australia to serve their sentence of seven years transportation. Part 2 will look at life recalled by later Hull people who settled Australia as free men and women in the 19th century.

On

this day (13th May 1787) a party of eleven ships, their crews, men, women, children,

marines, and convicts left Portsmouth for Australia. Under the command of

Captain Arthur Philip, they were to establish a new settlement. The journey of over

15,000 miles took upwards of around 8 months, finally arriving in Sydney Cove

from 18 January 1788.

Two

and a half years earlier on October 7, 1784, William Dring, a Hull boy believed

to be no more than 14 years old pleaded guilty to petty larceny at the Hull

Quarter Sessions. In return he was ‘sentenced to be transported beyond the seas

for seven years’. Dring was not alone. Also pleading guilty alongside him was

Joseph Robinson. He too received seven years transportation. A third individual

also implicated, was John Hastings. Hastings however denied the charges. Tried

by jury, he was later found not guilty.

|

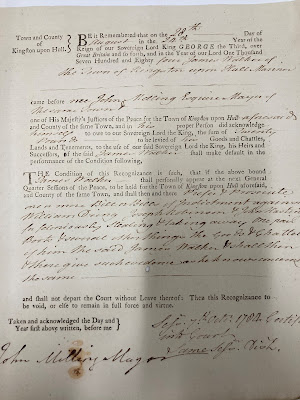

| Court case, William Dring - accused, 7 Oct1784 [Ref: C CBQ/60/19] |

Attempts

were made for Dring to receive a lighter sentence and even a pardon, perhaps

owing to his age or a reputed opportunity of employment in return for leniency.

Despite such attempts, the sentence stood, and the shackles remained steadfast.

At the same session, Robert Nettleton was sentenced to seven years

transportation for a similar offence, while Mary Atkinson also sentenced to

transportation ‘obtained his majesty’s free pardon’, though we are uncertain why

this was.

|

| Order for transportation, 1784 [Ref: C CQB/61/52a] |

The

First Fleet, under the command of Captain Philips was to establish a new (and

first) British settlement. They were among over 1,400 who set out making the

journey to the other side of the world, before their eventual arrival at Botany

Bay (now modern-day Sydney) on 19 January 1788. The ship they sailed on was the

Hull built vessel, Alexander.

For

those who sailed to Australia the voyage would be the first hurdle to overcome.

Hull man George Benson in his account

of transportation in 1840, described the voyage as fraught with misery. The

First Fleet however did make the voyage largely unscathed. Of the 1420 persons that

left, 1373 arrived at Botany Bay. The Second Fleet however which left for

Australia just under two years later was notorious for its poor conditions whilst

at sea. Many became ill, with a quarter dying before their arrival. Many

arrived riddled in lice, while forty percent of those that arrived died within

the first six months.

Early

settlers and convicts had to deal with the harsh conditions. Those serving

transportation sentences for example, worked from sunset to sunrise. They were

not paid. Punishment was physical. Lashes to the back were common. Some were

placed into chains and heavy irons to make their work harder. This, thrown in

with the heat and conditions could be truly awful. Female convicts were

punished with hard labour and solitary confinement on bread and water. Such

punishments would have no doubt impacted their mental health and wellbeing.

For

those that received seven- or fourteen-years transportation the options were to

return home or see out their days in Australia. Of course, those transported

for life, their stay was indefinite. Hull man, George Benson returned home to

Hull after his sentence and published his account of the ‘Horrors of

Transportation’. Others chose to remain, however. Those that left Hull

aboard the vessel Tranby all remained in Australia. For example, father

and son, John and Joseph Hardey were influential figures in the early

development of the Belmont area of what is modern-day Perth. Tranby House, on

the Swan River was built by John Hardey, one of those who left Hull onboard the

Tranby for Western Australia.

Those

who went out with the First Fleet looked upon the Australia’s Aboriginal people

with curiosity but also suspicion. And naturally this was very much

reciprocated by the Aboriginal people. It wasn’t long however until both sides

clashed. Shortly after the arrival of the First Fleet conflict between the

Cadigal but also the Bidjigal people broke out, despite official policy of the

British Government for the colony to establish friendly relations. There are no

accounts of any Hull settlers in direct conflict with Australia’s Aboriginals. Presumably

Dring, Robinson and Nettleton would have witnessed or perhaps participated in

these first conflicts between the two groups.

A

Hull man who emigrated to Australia via Melbourne recalled how it was not

uncommon for miners to carry firearms when travelling from Melbourne to the

gold mines for protection. The most documented encounter recorded with native

indigenous peoples by any individual is that of Hull’s John Jewitt, who was

taken prisoner by the North American Nootka tribe in what is today Canada’s

Pacific North-west. He was one of the first Europeans to spend time with

indigenous North American’s and his account of one of the earliest of their

life prior to western colonisation of North America. Click here to read more about John Jewitt.

Of

those three Hull men who went out with the First Fleet, William Dring remained.

He was however unable to stay out of trouble, perhaps he’d developed a

reputation among his peers. He was sent to Norfolk Island. The reputation of

Norfolk Island, set up as an off shoot by some from the First Fleet was

notorious among convicts, particularly those deemed unruly or trouble causers. Dring

was reputed to have started a fire on the Sirus. He is also reputed to

have stolen potatoes. Joseph Robinson too fell into trouble, but like Dring,

was this really his character? For example, it is said he killed pigeons that

were reserved for those most in need. Certainly, taking George Benson’s

account, one could argue Robinson and Dring, like others were in need given the

conditions and their treatment they endured.

|

| Extract from Quarter Sessions (1784) at Hull the recording the sentences of Dring, Robinson, Nettleton and Mary Atkinson [Ref: C CQB/61/51a] |

William

Dring remained indefinitely even after his sentence expired. In 1792 he married

Ann Forbes. Together, they had a daughter, Elizabeth (b.1794) and Charles

(b.1796) and settled in New South Wales. It is not known what happened to

William Dring. Dring may have died by 1798. Another theory is he’d left

Australia altogether with one suggestion William died in 1845 after drowning at

sea. However, we will never really know what happened to William Dring.

Look out for part 2 coming soon...

Neil

Chadwick

Librarian/Archivist

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments and feedback welcome!