The Ye Olde White Harte holds a special place in the fabric of Hull. Situated between Silver Street and Bowlalley Lane, and linked by a passage between the two, the unsuspecting visitor may easily walk past and not give it a second glance. For those who have frequented its premises it is a step back in time to when Hull remained confined to its medieval walls. At the time when no docks existed, ships would have fought for mooring space in the river Hull along the length of High Street waiting to load and unload their goods and cargos. The towns inhabitants of around 6,000 would have lived within the town walls. Beyond the walled town was open country. Many of those born in Hull would have lived, worked, and died in the town, perhaps never venturing far from its walls. For those that did leave, most were employed at sea, sailing to the Baltic, Northern Europe and beyond!

Whilst being well-known as favourite

among Hull’s watering holes, a must if participating in Hull's famous ale trail, the

Ye Olde White Harte has become known to many known as the place where in 1642, Sir

John Hotham, the then governor of Hull was said to have hatched a plot in the

‘Plotting Parlour’ denying King Charles I entry into Hull. Charles returned to

York before moving to Nottingham when on 22 August 1642 he raised his standard,

sparking the English Civil War. And the rest they say is history!

Stop there. Whilst Sir John

Hotham did indeed refuse Charles entry into Hull, the decision wasn’t taken in

the Ye Olde White Harte. The Plotting Parlour in the Ye Olde White Harte has

got somewhat confused with the actual plot hatched there some forty-six years

later.

The Plotting Parlour in the Ye

Olde White Harte takes its name from an event in 1688. In that year, on 3 December the Mayor, Aldermen along with leading figures of the town gathered at the then deputy

governors house, now the Ye Olde White Harte. They hatched a plan to overthrow

Hull’s Catholic governor. It is this plot that the Plotting Parlour takes its

name from, not that of Sir John Hotham’s refusal to admit Charles I into Hull.

Despite this, some continue to

believe, and indeed strongly argue that the Plotting Parlour is indeed where

Sir John Hotham decided to refuse Charles I entry into Hull in 1642.

So, owing to this confusion,

we’d thought we’d take a few minutes to put the record straight. Please note if

you are one of those who strongly believes the Ye Olde White Harte is indeed

the place where the plot was hatched to refuse King Charles I entry into Hull, you may want to look away now…

The myth

The myth about the Ye Old

White Harte being the residence of Sir John Hotham appears to have originated

in the 19th century. Despite many of its original features, the building

underwent significant alterations in 1881. Features like its stained-glass windows, which include the depiction of Sir John only adds to the myth.

Ye Olde White Harte

Evidence reveals (Historic

England) the building was not erected until after the Civil War.

It was built by William Catlyn, for Alderman William Foxley, a wealthy grocer

in 1660. Caytln was a bricklayer in Hull and responsible for several buildings

in the town, including Wilberforce House and probably Crowle House. Catlyn

himself is recorded in some of the documents here at the History Centre.

|

| The Ye Olde White Harte today |

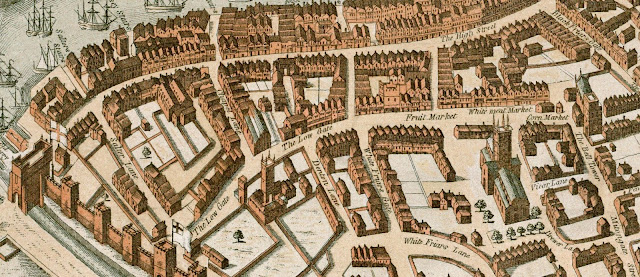

Hollar’s plan of Hull, c.1640

A clue to whether the Ye Olde

White Harte was around at the time of the English Civil War is perhaps revealed

in Hollar’s plan of Hull of c.1640. Looking in the vicinity in which the Ye

Olde White Harte is located (image below), there is a gap or space where the Ye

Olde White Harte sits today. Firstly, this isn’t unusual. Gaps or spaces were

common at this time in Hull. Despite being confined within its medieval walls, the

town had open spaces, particularly close to its walls. There were even gardens!

We must of course recognise not every building in Hollar’s plan is accurate and

therefore allow for some form of artistic licence on his behalf.

That said, Hollar appears to have had a knack to illustrate places from a viewpoint, impossible before flight. He must also have had some intimate knowledge of the town. Hollar depicts, for example, the busy river with most buildings lining Hight Street which for centuries was Hull’s commercial and economic hub. It was in the River Hull or 'Haven' that ships loaded and unload their goods and cargos whilst merchant houses and warehouses would have lined the river front and High Street. And Hollar knew this.

The Castle and Blockhouses on

the eastern side of the river are shown in detail, whilst prominent landmarks

such as Holy Trinity, the Suffolk Palace, the Guildhall all feature, though

this is perhaps to be expected being the town’s most prominent buildings at the time. Lister

House, the forerunner to Wilberforce House can also be identified. This begs

the question, with Sir John Hotham being governor of Hull around 1640, had the ‘Governors

House’ at the time been that of the Ye Olde White Harte, would Hollar have

included this? It was after all it was one of the larger and impressive

residences in the town back then.

The location of the old ferry

crossing across the river just south of the original North Bridge is shown, whilst

the cut on the eastern side of the river Hull, which is still there today, is also visible. Yet the same cut isn’t shown on Speed’s map of 1610. Nor is it

shown on the Cotton plan of Hull of c.1530. Hollar must therefore have had some

knowledge of the town. Whether he visited in person, we do not know.

Hollar had every reason to create

accurate as possible maps and plans. The demand for detailed and accurate maps

and plans was ever increasing. To military commanders their value would have

been a huge benefit, especially during the English Civil War, particularly whilst

employing sieges against a town, including that of Hull. Could the Earl of

Newcastle, for example, have held in his possession a copy of Hollar’s plan whilst

laying siege to Hull? There is no doubt the value of Hollar’s work is certainly

in the detail. Hollar added a scale which is measured in feet further

emphasising the need for accuracy.

‘Plot’ and refusal to admit

Charles I into Hull

In terms of where the decision

was made back in 1642 to refuse Charles I entry into Hull, such a decision would

have likely have been made in the Guildhall. Not the Guildhall we see today,

but the building that once stood at what is now the junction of Lowgate and

Mytongate, close to the King William statue. Since at least 1333 the mayor,

alderman and burgesses of the town met at the Guildhall. It was here

that decisions were made concerning the governing of the town. Prisoners were

tried and imprisoned here. High Street may have been the economic hub of Hull, but

it was the Guildhall that was the political centre the town.

Was Sir John’s decision not to admit Charles a plot as such? Sir John was appointed governor by parliament and to act on behalf of and under parliament’s instruction. The decision to refuse Charles I entry into Hull was that of Parliament. Sir John was instructed not to admit any forces into the town without orders from Parliament. Sir John, the Mayor, the Aldermen together with Parliament knew Charles wasn’t coming to Hull to sightsee, nor was he nipping in for a quick cuppa and a catch-up with friends. He coming to Hull to for one reason and one reason only. That was to secure the towns arsenal, which outside of London was the largest in the country. And being a trading port with connections to northern Europe and beyond, Hull provided Charles with a secure port to land supplies and men should war be declared against Parliament.

Sir John had personal reason

not to admit Charles. Beef and existed between the two going back

to 1640 when Sir John was removed from his first post as Governor of Hull by

Charles following repeated conflicts with Charles over ship money. Charles also

threatened Sir John with hanging if he continued to oppose Second Bishops War

with Scotland in late 1640. Mindful of this, Sir John knew the personal risk of

admitting Charles into Hull, which could have easily ended with his execution.

The feud between Sir John and Charles wasn’t exactly secret and this would have been known to Hull’s Mayor and Aldermen. This, along with Sir

John’s orders from Parliament would have hardly been a secret as such.

Knowing bad blood existed

between the two, and the fact that Parliament appointed Sir John as governor

with instruction not to surrender the town or its armoury without direct

instruction from Parliament, the decision to refuse Charles entry may well have

weighed somewhat on the minds of Hull’s townsfolk. Being declared at traitor by

the King wasn't something to be taken lightly. But the idea of a ‘plot’ or ‘plotting’ indicates

some sort of secrecy. Sir John’s feelings towards Charles must have been one of

the factors which influenced Parliament to appoint Sir John as Hull’s Governor

in the first place. This, and the fact Sir John was governor previously made Sir John the obvious choice. Parliament

must have therefore been confident in Sir John securing the town for them. Had the town not been secured for Parliament then the outcome of the Civil War may have been very different!

Some may argue Sir John was

somewhat undecided on this loyalty. He was after all ready to switch sides to

the King in 1643 because of Sir John’s deteriorating relationship with Parliament

due to Parliament’s reluctance to provide money to garrison Hull. However, there

was little to suggest Sir John was sat on the fence in 1642.

In 1688 however things were different. The towns Catholic Governor was planning to arrest Hull's Protestant officers and soldiers. In order to the turn the tables against Hull's Catholic Governor a plot was hatched. This plot was devised in the Deputy Governors house (now the Ye Olde White Harte) by Hull's leading Protestant figures. But in order for it to succeed it had to be done in secrecy, whereas 46 years earlier, Sir John's intentions not to admit were arguably less of a secret hence the idea of a plot against Charles being less likely.

Conclusion

The building we now know as the Ye Olde White Harte wasn’t built until after the Civil War. This should be enough to disprove the Ye Old White Harte as being the place where Sir John Hotham plotted to refuse Charles I entry into Hull. Everything therefore points to the ‘Plotting Parlour’ taking its name from plot conceived in 1688 to overthrow Hull’s Catholic governor.

We must also question whether a plot was even devised in the first place knowing Sir John’s clear instructions from Parliament and the bad blood that existed between him and Charles. The town of Hull may have initially had some reluctance to accept Sir John as the Governor for second time in 1642 but yielded to Parliament wishes. Perhaps Hull’s townsfolk were hoping a last-minute intervention would reconcile Charles and Parliament. However, by this time Charles had relocated to Oxford, and with each passing day any reconciliation receded. Hull’s mayor and Aldermen must have realised the implications, and quite possibly what was to come.

Unlike Sir John who had clear orders, those conspiring to overthrow the

Catholic governor in 1688 had every reason to act in secret. The Catholic

governor was planning to arrest Protestant officers and soldiers of Hull’s garrison.

And it was in the Plotting Parlour that the plan was hatched to turn the tables

on Hull’s Catholic Governor and arrest him first. Secrecy was therefore the

upmost for this to succeed. This, along with the fact the Ye Olde White Harte

wasn’t built until 1660 but also being the deputy governors house in 1688 is

more than enough to confirm that the Plotting Parlour relates to the plot 1688,

rather than the alleged plot to refuse Charles I entry into Hull in 1642.

Neil Chadwick

Librarian/Archivist

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments and feedback welcome!