Throughout Hull’s history mercantile enterprise has shaped the narrative and character of the city. The history of Hull’s commercial success can be witnessed in the city’s chronicle of charters and the continuous provision of licences allowing the merchants of Hull to trade internationally, providing this country with goods and sustenance. From the city’s formal beginnings as a port established by the monks of Meaux Abbey in the 12th century to the present city, the growth of maritime trade and the development of the city are closely connected. What follows is an examination of how Hull played a prominent commercial role in England’s experience of dearth - a prolonged scarcity of food - and subsistence crises of the 1580s and 1590s.

In the later 1500s, the country’s population grew continuously, and there were chronic uncertainties in food availability and inequalities in access to food. There were repeated episodes of unseasonable weather in this period. The Little Ice Age - a prolonged period of cold weather in the northern hemisphere, lasting approximately from 14th to 19th century - saw a long-term drop in temperature when winters were colder and seasons unpredictable (Kelly & Ó Gráda, 2014). Early modern England was still essentially an agricultural and climate-sensitive nation; its population was generally reliant on the raw materials and food goods derived directly from the land.

Harvest failure could be brought on by seasonal disruptions of heavy rain or freezing temperatures. Disparities of food availability could occur even if food was available, either through unemployment or mere inflation of prices. Early modern England struggled to produce enough food resources to feed a growing population and it was inundated with large scale vagrancy and poverty, malnourishment and illness made worse by the relentless inflation of tax. Food scarcity was already a worrying prospect without the addition of an uncertain climate. What is seen in late 1580s and mid 1590s is adverse weather worsening the disparities of food availability. These weather events would disrupt the germination of October sown crops and ruin the prepared spring fields, as would the “sudden freaks of nature: June frost, the violent hailstorm, the sudden deluge that submerged the meadows as hay was being gathered.” (Pounds:1994,176). Internal market networks were ultimately dependent on the lands from which raw materials were drawn. The reality for everyday people was that the land was their ultimate resource; their subsistence was often under their own feet and when hardship occurred its disturbance was immediate.

The mechanisms of grain markets relied upon supply and demand; but if there was no grain, no flow of money, no ability for those who lived close to the land to make money, then the market would fail. To cope England looked to its foreign neighbours to provide grain to feed its people. An effective, organised, approach to managing and securing the supply of grain to everyday people was required.

|

| Map taken from R. Davis The Trade and Shipping of Hull, 1500-1700, illustrating Hull’s international trading patterns |

In the 1580s Hull was in need of additional food supplies. In a series of miscellaneous letters, the impact of dearth and its ramifications on the city’s social order can be established. A letter from Lord Huntingdon, the president of the Council of the North, dated December 1586, identified Hull’s residents as being “greatly distressed for the lacke of corne” and that,

there may be some meanes be found in some sort to relieve them, I would wishe youto cause survey to be made of the corne remayninge within your towne in the merchants hands, and upon view therof to deale with the said merchants hands in such effectual sort, that they will be contented to serve the poore of your sayd towne with corne at a reasonable rate and if those in your towne beinge sufficiently provided for, the aboute you may likewise be furnished at lyke reasonable prices. (BRL/68)

The merchants provided a local benefit within the national context; the authorities were to search the warehouses and stores for any grain and to sell it at a reasonable price so that the poor people might have the opportunity to buy grain and be sufficiently provisioned.

|

| A letter from Lord Huntingdon to the Aldermen of Hull, requesting for the collection and distribution of grain in Hull, 16 Dec 1586 [C BRL/68] |

1586 was distinguished by its unusual weather and general dearth. Early in the year, a letter from the Queen’s Council at Greenwich to the aldermen of Hull gives permission for the residents to eat fish in the time of Lent - a time of religious fasting when annual stores of food start to run low. It reveals the fear of grain shortage within the town and reminds us that the repercussions of dearth went beyond human hunger,

and rather in respect of the late great mortallytie of shepe, and other kynde of great cattle generalie almost throughout the whole realme: and of the Darthe and skarcitie alsoe of other kynde of vycctualls at this tytme and for meanes to the better performance here of wee are to [remember] unto you that your owne example in the straight kepingene of those orders in everie of your owne howses will greatlie further the observing of the same amonge the meaner sorte. (C BRL/70)

The ‘general dearth’ of the country saw the implementation of firm dearth orders to be obeyed, and that those who held positions of authority within the city were to set examples for the citizens to follow. The instructions in these letters indicate that Hull is a city with provisions; there is an impression that Hull had the ability to provide for itself and could counter the late 1580s subsistence crises.

Hull’s expertise in trade, especially its connections with Danzig corn merchants, was fundamental not only to the town’s prosperity but to the whole country’s supply of corn. Looking first to its own body of agricultural land, Hull was granted a full and free licence in 1576/7, to “buye, within our counties of Yorke, Lyncolne, Northfolke and Kingeston upon Hull or any of them, from tyme to tyme, within the space of twentye yeres nowe nexte ensewinge, twentie thowsande quarters of grayne,” (Boyle, 85). It breaks down the request to say that this quantity is to consist of five thousand quarters of barley, malt, wheat and peas and beans. As grain goods were a valuable commodity, where the state could profit from tolls and taxes on any transportation or selling of the goods, the licence was a reassuring gift to this northern port. Here we see evidence of trade in local agricultural produce expanding into the national grain market; grain goods are no longer staying within immediate vicinities but are being transported to areas of need and want.

In the 1580s, it is estimated that 2,500 tons of cargo was owned in Hull, 18 ships could carry 80-100 tons and larger ships were now routinely adventuring to France, Spain and into the Baltic. By the 1590s England’s need for grain and the nature of Hull’s commercial and geographical positioning, meant that during this later subsistence crises the city’s importance in the country’s market network became evident. Hull’s position, neighbouring counties with agrarian and business interests, navigable rivers and smaller market towns, meant that the Tudor city had a favourable situation of being a port dominating its agricultural hinterland. Hull’s location allowed for the maritime trade routes, into the Baltic and principally with Danzig, to become the main routes of foreign grain coming into the north of England. Between the 1590s and 1620s, the Baltic trade began to expand, especially in the cloth trade and the expansion of trading bodies like the Eastland Company or the Merchant Adventurers’ company. The port saw quantities of wool, wood, coal and tin etc. passing through, however during the famine years of 1595-7 great quantities of Baltic grain were imported - most likely distributed to London.

There was such a demand for grain that on the 13th May 1597, Lord Howard wrote to the city’s aldermen requesting that ships containing corn would be allowed into the port’s haven excused from the restraints laid on. Certain “shippes of Danzick, Copen-Harben. Scotland and Holland that of last had brought corne to the port of Hull” to relieve “the inhabitants of that towne”, were to continue their voyage without the restrictions of foreign trade so that they may “return with more corne” and be “freighted bountiful of corne” (BRL/118). The plea to allow foreign trade to go without restrictions, which may affect the prices of homegrown crops and weaken Hull merchants’ transactions, could be read as a sign of desperation. There is an awareness that dependency on foreign trade was expensive, it could damage domestic agricultural efforts and could be manipulated for the ‘strangers’’ benefit.

|

| Letter from Lord Howard to the aldermen of Hull, requesting that foreign ships containing corn could pass through Hull’s port without taxation, 13 May 1597 [C BRL/118] |

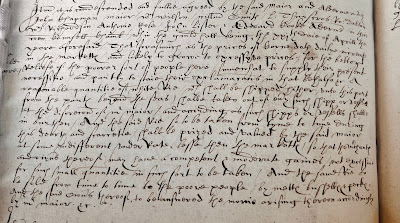

On the 21st of May 1597, the Bench Book notes the prices of grain in the market had inflated so much that the ‘poorer sort’ were unable to buy the victuals needed. It states:

That forasmuch as the prices of corne doth dailye increase in the market and likely to growe to excessive prices. For the better reliefe of the poorer sort of people here, in so much as to supply their present necessitie and partly to staie their [exclamation in their] behalfe & a reasonable quantite of white rie which shall be shipped hither unto this port from the porte beyond the seas & shallbe taken out of every such shipp or vessel at the discrecion of the Mayor, […] And the said rie for to be taken from tyme to tyme during this dearth and scarcetie shallbe prized and halved by the said maior at some indifferent under rate lesse than the markette for the inhabitants [of the towne] therefore may have a competent & moderate gain of, not excessive for such small quantitie […] [C BRG/2/305b]

The ships in Hull’s harbour were subject to a search and removal of excess grain goods. The Corporation, many of whom were ship owners, were given authority to conduct this act with the aim to relieve the poor of their lack of corn. The daily increase of prices was expected to become excessive; this preventive measure was almost an act of legally engrossing (buying up the grain quantities with the intent to sell again), but, rather than increase the already inflated price, it was to reduce and create a sense of availability and equality within the town’s market. The grain is being brought into the port town and through this authorative measure is dispersed as local demands require it to be - the grain goods are remaining in Hull thanks to mercantile enterprises giving access to the sought after victuals.

|

| Entry into Bench Book IV, detailing the inflated prices of corn victuals and the needs of the poorer sort, 21 May 1597 [C BRG/305b] |

What has become evident is that due to Hull’s location and its merchants’ ability to exploit the Baltic and continental trading routes, the early city found itself in a prosperous position. There were opportunities given to Hull by legislation and by orders to require provisions, whilst a significant proportion of the country remined in a corn and grain good deficit. There is little mention of Hull’s response to the climate changes of the Little Ice Age, yet throughout each episode of scarcity Hull looked to care for its citizens and manage the immediate response to hunger, aiding a reprieve from the looming consequences of subsistence crises. Overcoming the ‘unseasonable’ 1580s dearth, Hull set its own precedence in serving its community whilst balancing the nation’s general need. This is seen in 1590s crises when corn trading with the Baltic continued to economically grow and Hull authorities again sought to feed their citizens. The mercantile port of Hull was a part of early instances of globalization, spurred on by the effects of climate and the dietary needs of a hungry country. The city played an important role in the early modern agricultural market network; it connected domestic trade to foreign, overcame disparities in the northern famine-sensitive areas and fundamentally maintained links between the nation’s urban centre and the hinterlands immediately facing the consequences of subsistence crises.

Felicity Wood (University of Hull)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments and feedback welcome!