On the 14th January 1926 Lady Constance Wenlock (nee Lascelles) writes from the family home at Escrick Park, Yorkshire, to her daughter, Irene Constance Lawley who is residing in India with her husband, Colin Forbes Adam, a British Civil Servant working for the Indian Civil Service:

...when I am dead, or before any wet day or empty evening, you can read anything you like of letters kept and of my letters that have been returned to me by executors. I have destroyed everything that ought not to be read either on my account of someone elses. [U DDFA3/6/1/257]

Earlier in 1921 she writes:

I am afraid my very interior life must make very dull letters. But if you are leading an interior life the minutest details of it will not seem dull to me, I should like to know what you are playing and what you are reading. Of course, most of all what you are thinking and feeling, and you have a happy knack of generally letting that transpire. It runs easily from the tip of your pen. [U DDFA3/6/1/65]

Written between the wars, and far from ‘dull’, the letters of artist and writer of poetry, Lady Constance Wenlock reveal much about an unstable period in history seen through the eyes of a fascinating, imaginative woman with aristocratic connections.

Equipped with her typewriter and ear trumpet, she not only writes at length about politics, the partition of Ireland, Socialism, Russia and strikes but also about men, women, love and relationships, childbirth, birth control, and art and literature. However, almost 100 years later, and armed with our knowledge of history, her candid expressions regarding herself and her acquaintances, also reveal the stories of those who were not part of that privileged, affluent society. Amongst the engaging gossip, philosophies of life, love and political ideologies, the polite conversation also exposes classist and racist attitudes, and a chilling endorsement of eugenics.

In some ways these letters become a form of ‘skeleton diary’, like that which Constance advised Irene to keep as a record 'for future generations':

|

| Extract from letter, 6 Jan 1924 [U DDFA3/6/1/214] |

For the purposes of this blog I have selected a small number of letters from the collection that I hope do indeed help ‘reconstruct’ her life and that of the period for future researchers.

The Mirror Inside Me

My darling I do understand all you feel about ambitions. I used to think just the same only with extra vehemence because in the 70s and the 80s of the last century there was more opposition to the idea of a woman having any vocation, beyond being a wife and a mother and a housekeeper. I was determined to be not only an artist but a philosopher, a litterateur, a poet, a novelist. Then I had ambition for making society, for creating a salon. I succeeded in nothing, but now it is curious that I do not mind. I feel now that if you are happy, I do not want anything else. (Extract from letter, 31 Oct 1923 [U DDFA3/6/1/190])

A year later, despite the effects of aging and struggles with increasing deafness, she is still driven by her love of painting:

|

| Extract from letter, 16 Mar 1924 [UDDFA3/6/1/232] |

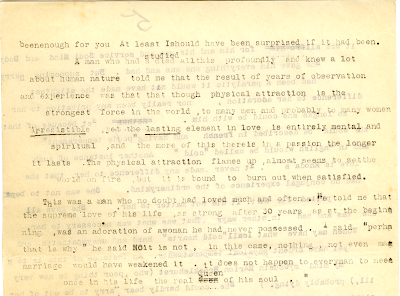

Women and Men, Love and Relationships

The letters cover many subjects, but one of the most engaging aspects of her writing are her contemplations on women and men, love and relationships. Reading them almost 100 year later it is easy to get drawn into her world, as if she is a fictional character from a classic novel of the early twentieth century. In fact, the letters very much lend themselves to a character study for a book, or a film or stage production. It’s easy to imagine them as a one woman play, a solo tour-de-force, with the letters as the script.

To her daughter, Constance often reflects on the pain endured by women and motherhood:

|

| Extract from letter, 11 Apr 1923 [U DDFA3/6/1/71] |

It is also interesting to see how open Constance is with her daughter when discussing intimate relationships between men and women, often including references to acquaintances, in gossip-like assessments. We have to remember these letters were originally addressed to Irene privately and not meant for public view and, in that sense, they are a valuable insight into the private thoughts of a woman of her time.

|

| Extract from letter, 9 May 1921 [U DDFA3/6/1/74] |

Constance values her female friends and finds them ‘the most indispensable’, particularly those founded on ‘admiration’. She indicates her annoyance with recently married Margaret Talbot who ‘patronisingly’ suggests otherwise, as the following quote illustrates:

Perhaps you have not been very fortunate in your men friends and she insisted that a man friend was always worth a hundred of a woman friend. I said rather sharply "if by men friends you mean lovers, of course that may matter most, but if you mean friends literally as a friend it is rare that a man can be as much to one and as close to one as a woman" (Extract from letter, 15 May 1923 [U DDFA3/6/1/153])

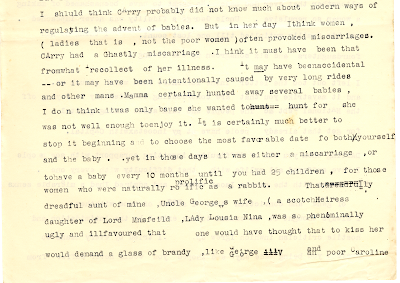

Childbirth, Twilight Sleep, Chloroform and Cocaine, and Horse-Riding as Birth Control

Of particular value to researchers might be the letters which record Constance’s recollections of the experiences of women around this period as regards childbirth, pain relief, and how women dealt with the lack of birth control:

| Extract from letter, 30 Apr 1923 [U DDFA3/6/1/152] |

In the following letters Constance indicates she may also have been given cocaine as pain relief, and there is an indication that pain relief varies according to a woman’s income:

|

| [11 Apr 1921, U DDFA3/6/1/71] |

|

| Extract from letter, 19 Apr 1921 [U DDFA3/6/1/73] |

There is also an interesting account speculating on the use of horse-riding to provoke miscarriage as a form of birth control. The letter then evolves into comments about her ‘ugly’ aunt. There are other instances in the collection that demonstrate Constance’s willingness to share her thoughts on anyone she regards as ugly, including children:

|

| Extract from letter, 18 July 1923 [U DDFA3/6/1/168] |

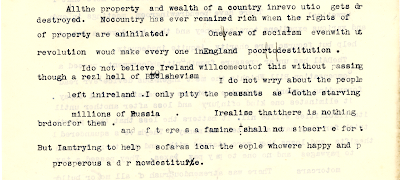

Fear and Politics in the Interwar Years

The interwar years, during which these letters are written, saw the collapse of the Liberal Party, and Labour becoming the main opposition to the Conservative Party. Women over 30 had received the vote in 1918, providing they met certain property qualifications. Resistance to British rule led to the partition of Ireland in 1921, the Russian Revolution paved the way for Communism, the land-owning aristocracy were in decline and the number of men killed in World War I had impacted the workforce. Lady Constance Wenlock found it difficult to find good quality servants, and we can see that political events of the time led her to fear for the future and, although she has some concern for the poor, this is selective:

|

| Extract from letter, 18 Apr 1923 [U DDFA3/6/1/150] |

In the same letter, Constance continues:

I have never appreciated warmth and comfort in my life as I have all this winter while thinking about homeless people of Ireland.

|

| Extract from letter, 25 Apr 1923 [U DDFA3/6/1/151] |

|

| Extract from letter, 23 Mar 1923 [U DDFA3/6/1/145] |

Constance writes extensively about the situation in Ireland and the 1921 Miner’s Strike. The letters give an insight into how these events are perceived at the time by gentry, landowners, and those close to the aristocracy. They also indicate she is aware of her privileged position in society.

As to taking care of myself, I feel ashamed to be so comfortable when almost everyone is in a state of acute privation. (Extract from letter, 9 May 1921 [U DDFA3/6/1/77])

However, it would seem Lady Wenlock would not consider education, or the introduction of dole, as a solution to hardship, and voices an admiration of Mussolini:

|

Extract from letter, 16 Mar 1924 [U DDFA3/6/1/232] |

|

| Extract from letter, 10 Dec 1923 [U DDFA3/6/1/202] |

|

| Extract from letter, 23 Mar 1923 [U DDFA3/6/1/145] |

|

| Extract from letter, 10 Dec 1923 [U DDFA3/6/1/202] |

Class and the Poor Little Kitchen Maid

Throughout this collection of letters there is a lot of material that would support research into perceptions of class during this period, or indeed, how some of these attitudes perpetuate today in a society where inequalities persist.

Lady Wenlock laments the erosion of class distinctions:

|

| Extract from letter, 3 Jun 1923 [U DDFA3/6/1/158] |

Also contained in the letters is a detailed account of a ‘poor little kitchen maid’, accused of being pregnant. The 16 year old girl is not referred to by name and has been sent to work for Lady Wenlock from St Hilda’s industrial school for girls in York:

|

|

| Extract from letter, 23 Sept 1923 [U DDFA3/6/1/184] |

Lady Wenlock would refer to the quality of employees sent from St Hilda’s again, this time suggesting the problems arise from inherited qualities:

|

| Extract from letter, 25 Feb 1924 [U DDFA3/6/1/228] |

‘The Very Low Type’ - A Warning From History

The letters make for uncomfortable reading when Lady Constance Wenlock recommends a book to her daughter, ‘The Revolt against Civilisation’ by Lothrop Stoddard. Stoddard was an American advocate of eugenics, a white supremacist and member of the Ku Klux Klan, whose work inspired the Nazis. This letter, written in 1924 is particularly chilling as an acquaintance suggests ‘a lethal chamber’ as ‘a way of doing good’ and Constance also reaches the conclusion ‘that multitudes ought to be killed off’ although she ‘cannot say how it is to be done.’

|

| Extract from letter, 21 Jan 1924 [U DDFA3/6/1/217] |

Lady Constance Wenlock died aged 80 in August 1932. She would not live to see where eugenics ideology and experiments with ‘lethal chambers’ would take the world just 7 years later.

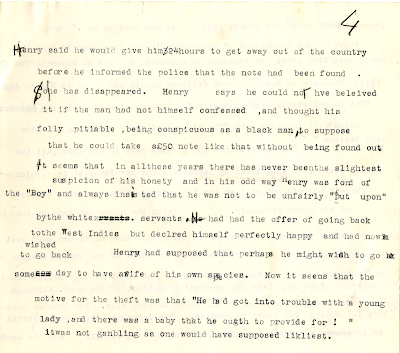

CASE STUDY: ‘DO YOU REMEMBER THE ‘BLACKAMOOR AT HAREWOOD’

By highlighting a number of letters in this collection, I hope to have demonstrated how the voice of one woman, and her candid personal accounts, can aid researchers and creative writers in uncovering real lives and lived experiences of the period. One particular letter written on the 6th January 1924 became an important piece of the jigsaw in research by Audrey Dewjee for the ‘Historycal Roots’ project, which aimed ‘to raise awareness of the black and mixed heritage people who have played a part in shaping society.’ Bertie worked as a footman for the Lascelles family at Harewood House. After stealing £50 Bertie was forced to leave his employment. The reasons why he stole the money are revealed in this letter written by Constance on the 6th January 1924.

The research of ‘Historycal Roots’ would lead to an exhibition at Harewood House about George ‘Bertie’ Robinson and uncover the story of what happened to Bertie and his child after leaving Harewood. You can read about the research here: Bertie Robinson of Harewood House.

You can read more about Lady Constance's daughter Irene in the blog Nursing in a Crisis: Irene Lawley and the Escrick Park Auxiliary Military Hospital.

Andrea Lamb (Archives Customer Experience Advisor)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments and feedback welcome!